Social Policy, Poverty, and Inequality in the United States

The Atlantic Academy’s Road to the Elections No. 6

Christian Lammert, Free University Berlin

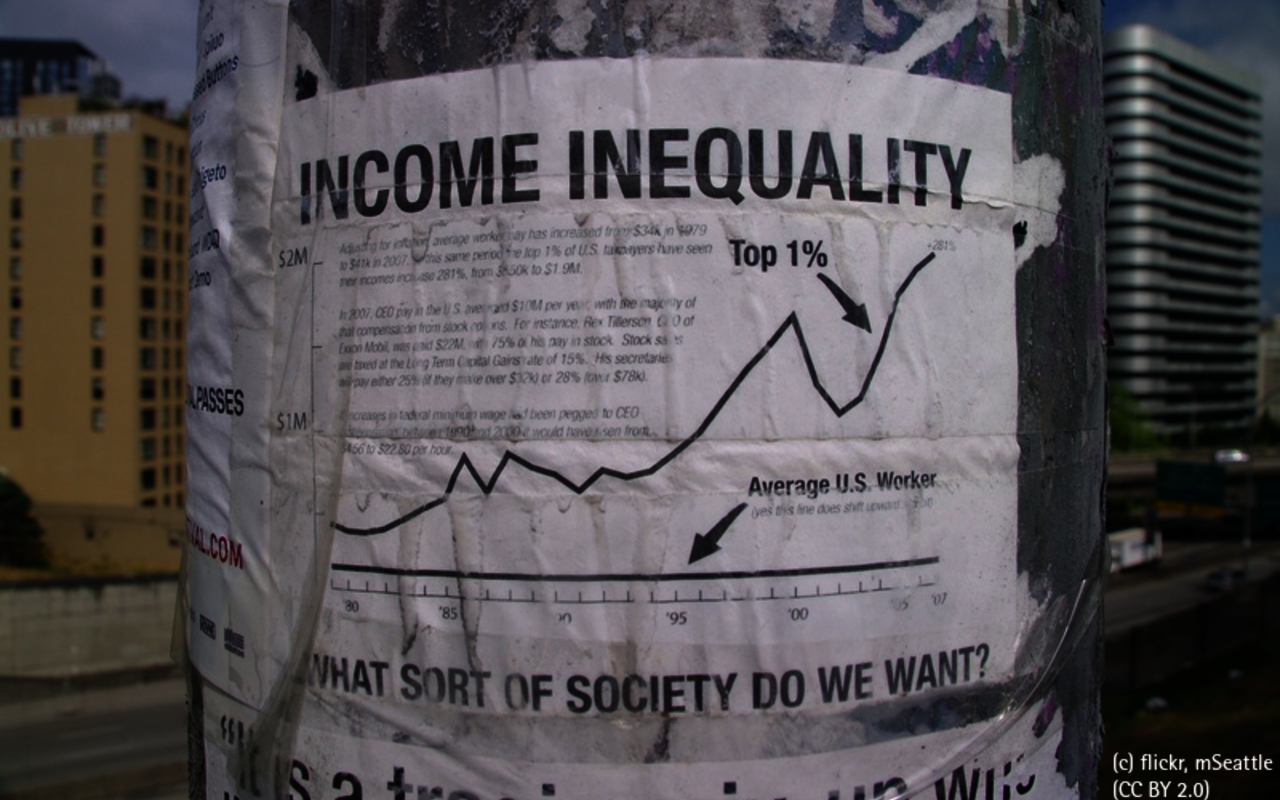

Bildnachweis: (c) by mSeattle, flickr, "Income Inequality".

About this Series

On November 8, nearly 200 Million registered voters are called upon to elect the next President of the United States of America, all 435 members of the House of Representatives as well as thirty-four of the one hundred senators. As in 2008, there is no incumbent, which is why both parties, the Democrats and the Republicans, will determine their candidates in primary elections. Thus, maybe fundamental changes but at least new accents in some policy fields should be expected.

With a monthly publication series, the Atlantic Academy will focus on this road to the elections in November. Political and economic scientists analyze policy fields as well as their roles in the (primary) elections and formulate expectations for a new presidency and Congress.

In 2013, President Obama described rising income inequality as the “defining challenge of our time” (White House 2013). And he seems to be right, U.S. citizens today live in an unequal society. Inequality is greater now than it has been at any time in the last century. At the same time, the dimensions of that inequality appear familiar and depressing. A smaller share of national income is going to wages and earnings, and inequality within that labor share is widening. As a result, there was no wage-growth in the last 35 years. Middle-income workers earn no more now than they did in the late 1970s and those in the low-wage sector have even lost ground since then.

Bernie Sanders has built his primary campaign on the topic of inequality. He is calling for political revolution ending the influence of the super-rich on the political decision-making process. He borrowed the reference to the top 1 percent from the Occupy Wall Street movement, indicating that the distribution of wealth and income has grown more unequal in the last 20 years and that this development poses a real threat to the quality of democracy in the United States. This is the first time in recent US history that a self-described ‘Socialist’ runs for a presidential nomination and is successfully mobilizing on this topic. Sanders has presented himself as an advocate for social benefits of social assistance programs, he is pushing for a universal health care system and wants to reform the educational system in order to make education affordable again. His positions on health care, social and education policy are much more progressive in comparison to Hillary Clinton. Programmatically, she is more in line with more centrist Democratic reform proposals in those policy fields, although the primary contest with Bernie Sanders clearly has pushed her towards a more progressive position especially on health care and education.

On the other political side, the Republican Party is struggling with a candidate Donald Trump who has no coherent social policy program so far. His positions are more or less a collection of impulsive anecdotes partly contradicting each other. He sometimes calls for repealing Obamacare and replacing it with Health Savings Accounts, what essential would mean to privatize health care. In other interviews, he seems to be satisfied with Obamas stricter regulation of the private health insurance market and calls for extended public health care for poor people. The same patterns apply to other social policy programs as well. Trump, at least in the primary season, seemed to follow a more populist strategy that tries to adapt to public sentiments instead of providing a more coherent reform proposal. In general, his ‘Making American Great Again’-approach is more focused on economic policy, a strong indicator for a more workfare base approach to social policy.

From a social policy perspective, the more interesting game is played on the side of the Democratic Party. A self-proclaimed ‘Socialist’ is mobilizing around topics like inequality; he is calling for a political revolution with references to the welfare regime in Denmark as a role model for social policy reform. How has inequality developed into such a hot topic in the ongoing presidential election campaign and why are the people so upset with the political establishment in Washington, D.C.?

Between 1979 and 2007, the real income of the richest 1 percent almost tripled, while the real income of the median household has risen only by about 25 percent—and that is mostly due to an increase in labor force participation and hours worked. Inequality in wealth is growing even more compared to income inequality. The richest 1 percent owns about a third of the nation’s wealth; the top 5 percent owns over 60 percent. That is what we have learned from Piketty and his colleagues. Additionally, the financial and economic crisis of 2008 took a big bite out of middle-class wealth—much of that in home equity—and the gains of the recovery have flowed almost exclusively to the rich.

To make matters even worse, demography and geography widen these gaps for many. The gender gap in wages, income, and wealth has closed very slowly, and most of that progress is driven by the collapse of male wages rather than real gains made by women. The racial gap in wages, income, and wealth has closed little, and it has even widened for those caught up in the startling and racialized spike in incarceration. While racial segregation in the cities has decreased somewhat over the last generation, economic segregation—the likelihood that someone lives in enclaves of wealth or poverty—has increased. Economic or social mobility altogether remains weak in the United States.

But what has caused this development? Generally, conventional explanations are focused on two narratives: The first: somebody took the money. This story stresses the mammonism of Wall Street and the tax cuts of the Bush-Administration. The result: a plutocracy determined to claim more than its share of private wealth and to shoulder less than its share of public goods. The second narrative: something happened to the economy. This narrative has globalization and technological change as its major suspects. I will not go into the details of both narratives here, but these narratives are not so much wrong as they are misleadingly incomplete, inattentive to longer-term historical trends, and to the political choices made across that history. A fuller explanation needs to consider the political and economic conditions that prevailed right after the Second World War. At that historical moment, the United States displayed much narrower gaps between the rich and poor. Economist Paul Krugman called this the great compression. The gains of economic growth were much more broadly distributed in the time of the Post-World-War II consensus or the golden time of the welfare state. In addition, working families—at least white working families—enjoyed much greater economic security during that time period.

This time and setting was the achievement of political struggles and policy choices that had built a foundation and a structure for shared prosperity. As a consequence of the political response to the Great Depression, the inequality of the early twentieth century actually began to close before economic growth took off in the 1940s.. Due to this response, federal support for collective bargaining rights sustained a rise in labor organization that dramatically improved the bargaining power of workers. Other political elements of the New Deal—ranging from Social Security to the minimum wage—secured a floor for working-class incomes. New social movements—especially civil rights and second-wave feminism—then further surrounded that floor by closing off avenues for discrimination.

At least since the 1970s, that structure and common ground has essentially collapsed. This collapse is often described as an unfortunate but necessary response to changing economic conditions: the world has become a more competitive place. As a result, the policies of the New Deal—and the costs they imposed on business—had to go. But political choices, not economic necessity, dismantled the New Deal: steep cuts in social spending, the political abandonment of organized labor, deregulation and privatization, tax cuts, punitive cycles of unemployment—all justified in the name of lowering business costs, strengthening economic efficiencies, and unleashing markets. Such arguments, of course, camouflaged the real goal of the pushback against the New Deal: a redistribution of income to the top via the erosion of the hard-earned bargaining power of ordinary U.S. citizens. Rising inequality was not a lamentable side effect of America’s new policy framework; it was its intent.

However, income and wealth inequality are just one side of the picture. The official poverty rate increased from 12.5 percent in 2007 to 15.0 percent in 2012, and the child poverty rate increased from 18.0 percent in 2007 to 21.8 percent in 2012. The current poverty rates for the full population and for children rank among the very worst over the last 15 years. The latter increases in poverty, although substantial, would have been yet larger had the effects of the labor market downturn - as a result of the financial crisis of 2007/2008 - not been countered with aggressive safety net programs by the Obama administration. Unemployment benefits and spending on food stamps have been extended massively. Absent any safety net benefits in 2012, the supplemental poverty measure would have been 14.5 percentage points higher. In the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s, the poverty rate was also approximately 15 percent, even though these were more moderate downturns. Although the latest recession was more extreme than these prior ones, the rise in poverty has nonetheless been partly held in check by a responsive social policy reaction of the Obama administration.

The safety net is increasingly fashioned to incentivize market work. As the Earned Income Tax Credit expanded in the early 1990s, households that increased their market earnings were better protected from sharp declines in their safety net support, a reform that ramps up the incentive to pursue market earnings. This rate of “relief falloff” has continued to grow gradually smaller up to the present day. As a result, the safety net in the U.S. is now better constituted/shaped to encourage market work, which is precisely the type of safety net that many people want.

The safety net responded reasonably well to the challenges of the financial crisis of 2007/2008. It delivered substantial poverty relief during that crisis because a recessionary labor market generates precisely the type of need (e.g., unemployment) that the American safety net is relatively well equipped to handle, and the safety net was also modified in ways that responded well to the particular demands of this economic crisis (e.g., extended unemployment benefits).

The foregoing suggests a broadly deteriorating poverty and inequality landscape. Such deterioration is revealed across a host of key indicators, including prime-age employment, long-term unemployment, poverty, income inequality, wealth inequality, and even some forms of health inequality. The facts of the matter, when laid out so starkly, are quite overwhelming.

Social policy exists to dampen the impact of the market—including the inequality that follows from disparate patterns of education, employment, and opportunity. It aims to secure the income of workers, and to support the income of those who cannot work. On this score, the United States has sustained a very different boundary between the market and policies that deal with market failures than most of the other advanced welfare regimes. Many basic benefits, as can be seen in the case of health care, are more private than public. Plus, U.S. policies, following the expectation that security would and should flow from employment, are less generous across the board.

Even public programs increasingly favor workers over non-workers—a pattern evident in sustained support for payroll-based benefits and the Earned Income Tax Credit, alongside declining support for AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) and TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families)—in an era in which work itself is increasingly scarce, unpredictable, contingent, or temporary. Weak social policy is accompanied by weak labor market policies, and neither impose much of an obligation on private employers. U.S. social policy has few universal programs, preferring to fragment coverage and eligibility by need, contribution, age, family status, and geography. All of this is particularly true of the last generation of social policy which, pivoting on the repeal of AFDC in 1996, has seen the United States cut social protections more fiercely and more deeply than most of its peers.

These cuts would be less daunting if there were any doubt about the impact of social policy on inequality. But the historical record shows that the most ambitious social programs have made a real difference. We know, for example, that the policies installed during the “war on poverty” in the 1960s yielded a substantial reduction in poverty—bringing the national rate from about 25 percent to about 15 percent. And this occurred across an era in which the forces driving wage and income inequality and hence the task of reducing poverty, grew steadily. We know that the Social Security pension program has almost singlehandedly eradicated poverty among seniors. Before Social Security, almost 80 percent of American seniors lived in poverty. As Social Security contributions and payments became established early in the postwar era, poverty among seniors began to fall—and continued to do so under the Great Society, favored by the passage of Medicare in 1965. Since the program’s growth slowed in the 1980s and 1990s, poverty among seniors has leveled out at about 10 percent.

As mentioned before, social programs made a big difference during the last financial crisis. Programs such as unemployment insurance, the earned income tax credit, and food stamps kept about 41 million U.S. citizens out of poverty in 2012. The poverty rate (for all ages) in 2012 was about 16 percent; without these programs, it would have been closer to 30 percent.

These successes should not mask, however, the stark (and widening) gaps in social provision. Up until ‘Obamacare’ [Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act], the health care system had left tens of millions uninsured—while spending more and accomplishing less (in terms of basic health outcomes) than other countries. The U.S. trails the world (and not just its OECD peers) in the provision of basic family or sick leave. And the public education is compromised by deep local disparities in funding for K-12 schools, not to mention a full retreat from low-cost access to postsecondary education or training.

Cuts to social programs have only widened the gap between the poor and everyone else—especially the retreat from AFDC since 1996. By any measure, the TANF program is a weak substitute for the program it displaced. By the mid to late 1970s, AFDC reached about a third of all poor families, and over 80 percent of poor families with children. With the implementation of TANF, this coverage shrank almost immediately (1996-1997) to about half of all poor families and about two-thirds of those with children. By 2010-2011, only 20 percent of all poor families, and just over 27 percent for those with children, were receiving TANF assistance. Between 1992 and 2010 alone, one million more American children slipped below the poverty line. The share of Americans living in severe poverty (below 50 percent of the poverty line) has almost doubled since 1972.

Many of the programs that remain are poorly targeted, creating eligibility traps and gaps for those that might benefit from them. As a rule, social insurance programs (like Social Security pensions) are generous but poorly targeted, while means-tested programs are well-targeted but meager. As a result, American social policy closes most of the poverty gap for elderly families and individuals, for whom social security benefits flow to rich and poor alike. But it accomplishes progressively less for single-parent, two-parent, and childless families—for whom means-tested benefits are both less generous and less universal. The gap is especially acute for non-elderly childless families who—regardless of their income—rarely meet the eligibility threshold for public assistance.

The dismantling of the safety net comes just as the economic risks faced by families have grown massively. Wage stagnation, the loss of work-based benefits, employment insecurity, the rising costs of education and health care, and, more recently, a dramatic dip in housing wealth have merged to make economic mobility more elusive, income more volatile, and economic catastrophe more likely. Not only has the welfare state failed to adapt to these new realities, it has retreated from them and made things even worse.

And the results of all these developments can be seen in the presidential race 2016. People are upset with the economic development, criticizing not just how politicians reacted to those developments but blaming them to have implemented policies that have fostered those developments! That is the time for populists like Donald Trump! More and more people are not heard any more in the political process. The most affluent seem to have the most political influence. Even main stream political scientist like Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page “belief that if policy making is dominated by powerful business organizations and a small number of affluent Americans, then America’s claims to being a democratic society are seriously threatened” (Gilens and Page, 2014, 577).

Bibliography

Gilens, Martin and Bejamin I. Page (2014), Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interst Groups, and Average Citizens, in: Perspectives on Politics 12, 3, 564-581

Krugman, Paul (2009), The Conscience of a Liberal, WW Norton & Company

Piketty, Thomas (2014), Capital in the 21st Century, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

White House (2013), Remarks by the President on Economic Mobility, www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/12/04/remarks-president-economic-mobility (access 31.5.2016)

About the Author

Christian Lammert is Professor of North American Politics in the Department of Political Science at John-F.-Kennedy Institute for North American Studies. He received his PhD in political science from Goethe-Universität (Frankfurt am Main) in 2002 and taught there from 2002 until 2007. He published widely on social policy, the political system in the United States, health care reform in the U.S. and nationalism and regional Integration in a transatlantic perspective.